There’s something to be said for a week in Hong Kong: Our shin splints have given way to calves of steel and an uncanny ability to manoeuvre crowds. Our steamed dumpling radar is more or less bang on. And our Cantonese sucks.

The first achievement is entirely circumstantial. Hong Kong was built on a mountainside; our accommodation—a small concrete-floored apartment with Tetris perfect design, a comfy fold out couch, and the company of Dave’s friend Taylor, who actually lives here and is graciously putting us up for the week—is pretty high up the HK slope. We’ve had no choice but to walk up and down hundreds of steps every day, varying it up (one step, two steps, even three steps at once,) but never so much as to risk a nasty concrete tumble that might end as far down at the harbour, and would almost certainly end in an ambulance. But stairs here don’t get in the way of timely arrivals—local walking pattern do. Turns out bustle doesn’t always go hand in hand with hustle, and that Hong Kong pedestrians don’t much care for straight lines or uniform pacing.

Trying to pass a slow walker in a tight market area or confined metro space means anticipating a sudden horizontal movement, or full group fan-out, before it happens. In this city, an erratic mid-stride stop is as standard as a knock-off Rolex or purse (or in my case, a camera memory card and fake-nail-polish pedicure).

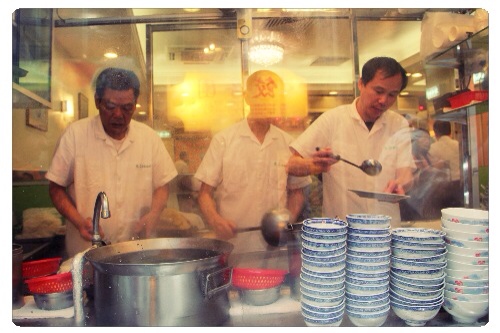

As for our newfound dumpling sense, it’s simple, really. We like dumplings, we see them, we eat them. Except that now we’re particularly good at finding local joints with long line-ups and short waits, and dumplings that range from truffle-filled to king prawn, and come in rice steamers, on celophane plates, or in soups. Sometimes we forgo a dumpling opportunity for a stick of street-served fishballs. It’s all a nice change from the bakeries, which overwhelm the streets, serve everything from ham and cheese rolls to sweet red bean buns and coconut cakes, and make you question how the locals can possibly stay so stick thin. The fact that “glutinous” is the full name of an item sold in these pasty shops is worrisome enough.

And about the whole language thing, we don’t feel too badly. Apparently, there’s little use in Caucasians attempting to master the 7 distinct Cantonese tones that transform what we might hear as a single word into two or three different ones, depending on how their vowels are pronounced. Many expat children born and raised in the city never learn the language at all. So, there’s been no friendly banter with store owners and cab drivers in Cantonese. Though after laughable amounts of time spent on escalators—the city is so automated that dozens of linked moving staircases take commuters up and down the streets of Hong Kong to alleviate traffic—we have more or less perfected our “please, hold the handrail.”

Not surprisingly, the name Hong Kong itself is a case of lingual butchery—a corruption of the words Hoeng Gong, or fragrant harbour, referring, as some historians suggest, to the island’s earlier export of fragant incense.

As we’ve learned, and re-learned, it ‘s all too simple to misread a culture you’re unfamiliar with. We spent yesterday afternoon meandering in and out of narrow market streets, taking in the China-red trinkets and fish heads and fake rubber abs, cameras in tow. One second I was snapping an instant-deleter of a blurry cat perched on a stall roof, the next I was shielding myself from the toothless old lady pummelling me from behind with ratty newspapers. It was her cat, naturally. I guess I’d gotten so used to people nodding yes to photos, that this time, I’d forgotten to ask. The result: one livid lady, one corrupt cat, and one case of public humiliation.

Or last week: At a local Dim Sumerie, the waiter sat us in a prime location between the air conditioner and the hall, then brought out a pot of tea, two tea cups, two sets off chopsticks, and a single ashtray-shaped bowl. We had the first three items figured out, but what to do with the bowl? Eventually, of all things, we settled on pouring a thin film of green tea into the ash tray, and dabbing our chopsticks in it. We had washed our utensils like this at the last dumpling restaurant … but we also and drank beer from delicate Chinese bowls and pelted each other with bottle caps (read: beer pong) while the chef had a Gangnam Style dance off with another customer. The look on our waiter’s face, and his prompt removal of the receptacle, told us that we had probably missed the mark. No more ashtray bowls for us.

Here, it is hard to say what is normal.

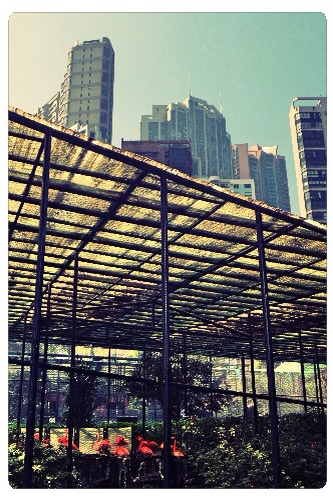

Scaffolding structures for entire high-rises are fashioned from bamboo, which is said to be sturdy yet slightly bendable, and thus resistant to winds. Coffee shops stand next to coffin shops in the Sheung Wan district. Winter temperatures run between 14 and 21 degrees, yet the mode d’hiver consists of Ugg boots, long pants and puffer jackets. “Helpers” from Vietnam mind the local houses, and children, and dogs. And even the Boston Terriers and Mini Schnauzers prance around in the kinds of sweatsuits and booties that make Canadian winter dog-walking look like an animal rights travesty.

And residents wear surgical masks over their mouths in public, not to avoid sickness, but because they are sick.

The local zoo is a burst of sloped jungle wedged between office buildings and fancy high rises (strange) and it’s absolutely free (even stranger.) Here, fancy Asian monkeys swing through the sky scrapers, exotic birds have human faces, and a group of orange flamingos feeds alongside neon ducks and adorable Asian mice, who become less adorable once you realize the are simply rats. (In my post-zoo days, I spent an ample amount of time deciding whether the nasty rodents were more a part of the exhibit or an infestation. Cases could be made for both—the “Eeeew raaaaats!” version perhaps more plausible than the “rats are part of the Chinese calendar and could very well be revered” story I had formed in my head. Eventually I asked. Turns out rats are rats are rats. And a free zoo is a free zoo, after all.)

But this bending of rules and disregard for common (ok, Western) practices is what we’ve come to love about Hong Kong. The city ooozes age-old Asian tradition with a mad case off Times Square. High rises near the harbour evoke a city of the future, as do automated female British announcements and frequent teleportation sounds on the metro, but the winding streets above all the business are full of smell and colour, the architecture a mishmash of momentary inspiration, and the whole thing kind off falling apart. The combination of it all—perhaps best viewed by ferry as it shimmies along the harbour—speak of a city 50 years into the future, glass buildings rising up into the heavens, pockets of crumbling culture still intact. So here’s to Hong Kong, the first stop on our trip, and the city we’ve affectionately come to know as Hong Concrete. Where sky-high buildings meet even loftier prices (a month’s rent for a 500 square foot apartment can easily seat you back 4,000 Canadian dollars.)

Where a harbour-front lot in the city can be found as quickly as the government can cart in rocks from the quarry and fill in the shoreline, thus repossessing and selling the waters at a price lucrative enough to keep income taxes lower than low. Where foreigners sit in air-conditioned rooms fingering scones and sipping on tea, while in the parks above them, locals carve out the silent motions of an age-old martial art. Where fog is smoggy and smog is foggy, and we might never find out which is which for sure. But we’d love to come back and try.

Linda

Jan 21, 2013 -

Hi maya. Really enjoyed reading your blog. Felt like I wAs there. Should send it to the New Yorker !!!

Marianna

Jan 21, 2013 -

Right on, Linda, I second both – feeling like being there and the NYer!

Twitter23

Jan 23, 2013 -

Hi, just wanted to say i liked this article. it was practical. keep on posting.